After the Second World War, the Hirschfelde open-cast mine, once developed by German (Saxon) authorities, ends up inside new Polish borders. At first, due to its location, it will be called Graniczna (Borderland). The name Turów would appear a moment later. The mine needed not only a new name, but a new crew. Many people formed it: volunteers from Upper Silesia, Polish miners returning from work in Belgium and France, and pre-war German workers.

The introductory part:

In May 1945, the Second World War comes to an end in Europe. The conferences of the “Big Three” powers determine the new course of the borders. Poland loses its eastern territories to the USSR and gains part of East Prussia, Western Pomerania, the Lubusz region and the whole of Upper and Lower Silesia. With it, Poland gains a piece of the historic Upper Lusatia, which, because of the shape of its borders, seemingly pressing deep into Czechoslovakia, would soon acquire the unofficial name of the Turoszów Sack.

The border on the Lusatian Neisse split the historical town of Gorlitz into a German centre and Polish suburbs, which now became Zgorzelec and began to develop as a separate centre. It severed the ties of the villages on the right bank of the river with another historical Lusatian town of Zittau. located on the left bank. It also cut across the Hirschfelde industrial complex, established by the Saxon government no more than three decades earlier.

In 1917, through buying up older plants from private owners, the Saxon authorities created an industrial complex consisting of an opencast mine, a power plant, a briquetting plant, workshop facilities, warehouses and a railway line connecting them1. In 1945, the Hirschfelde mine was located on the right, Polish bank of the Neisse, while the power plant and workshops remained on the German side and the whole complex was put under the administration of the Soviet Military Administration. In August 1946, the USSR decided to hand over the opencast to Poland, but without the technical inventory, which remained on the other side of the river. Poland also had to recruit new workers for the mine, replacing the 1,200-strong German staff. On 23 November 1946, Polish officials ended the technical examination of the mine, so that on 23 February 1947, a preliminary agreement could be signed to hand over the opencast to Poland, however, with a commitment that the mine would continue to supply the necessary quantities of coal for the German power plant2.

Thus, Hirschfelde became Graniczna, the Border Mine. The name Turów appeared a short while later, when Stanisław Kulaga, the Polish administrator of Turoszów, misspelled the name of the neighbouring village. On 18 June 1947, Hilary Minc, Minister of Industry and Trade, included this opencast mine in the register of Polish industrial enterprises3.

When the Polish delegates signed the handover protocol, new inhabitants were already settling in the Turoszów Sack area.

As early as May 1945, demobilised soldiers of the Second Polish Army, who had entered the area a few days after the Soviet army, were settling in Upper Lusatia with their families. A new life at this new end of Poland begins for the inhabitants of the Eastern lands annexed to the USSR. A certain group of Poles, but also Byelorussians or Latvians, who had been deported to Lusatia for forced labour in Nazi Germany, decides to remain. To ensure communication between everyone, German would remain the main language of communication at the mine for some time4. This mosaic of origins can be found in the first Polish street names of the growing settlement: German Street, French Street, a street of ‘People from behind Bug River’. Kurzańska Street still runs in front of the church of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Bogatynia: it used to lead to Strzegomice, which the first settlers called Kurzany, just like a village in the Berezany region in today’s western Ukraine.

On 1 September 1946, a group of 10 guards from the Dębieńsko mine in Upper Silesia’s Czerwionka-Leszczyny arrived the site. Once they have acquired their mining qualifications, they would begin to form a Polish crew. Konrad Dusza, who will soon take up the position of traffic controller at the mine, leads them. The number of Polish pioneer miners grows daily, gradually replacing the German miners, although the latter will still be part of the crew until the 1950s. More Upper Silesians join them, as well as Poles who emigrated for work in the mines of northern France and Belgium before the war.

The newcomers arrive first in Zgorzelec and then head south along the badly eroded road. Today, when the Turoszów Sack is again only accessible by this road, it is relatively easy to imagine what they saw on their way to their new homes. They passed the villages of Radomierzyce, Ręczyn, Krzewina, Bratków, which only a dozen years earlier had been Radmeritz, Reutniz and Grunau. In Działoszyń (formerly Königshain, hence the first post-war name – Królewszczyzna), they could see the slender silhouette of a baroque church from the road. Then less than ten more kilometres across the fields and the buildings of the biggest village began.

Its name echoed the promise of prosperity. In German, the village was called Reichenau: die Aue means meadows, marshes, reich is rich. The Polish administration called it Rychwałd immediately after the war, and in 1947, chose another, also rich-sounding name – Bogatynia5. In Poland, too, Bogatynia would be granted town rights.

But the newcomers had to forge their prosperity with their own hands.

– The proletariat of Rychwałd live and work in conditions so unpleasant that, despite work on my part and without help from higher factors, I am unable to prevent this

– complained Stanisław Kwiatkowski, chairman of the local branch of the Trade Union of Textile Workers of Poland, in a letter to the national council in Zgorzelec in November 1946.

He listed a whole list of ills:

We lack coal (even though we are already in the middle of winter); beds (stolen and taken away by looters); footwear (no rations were received); clothes (as mentioned above); communication (only a bad road is a connection); milk for children; hospital; reading room; cinema theatre; proper police care (four militiamen)6

In 1947 the local workforce numbered 356, a year later it was already 850. New employees of the mine receive 5,000 zlotys for development, but many of them lacked a housing in Bogatynia. They were accomodated in villages along the road from Zgorzelec, and walked to work – the mine gate is almost 4 km from the centre of Bogatynia – on foot. Basic food is brought for the crew by the mine’s staff on horse-drawn carts borrowed from military settlers, on days when they travel to the lignite industry inspectorate in Luban on business. It was only with time that a canteen was established, an inn called “On the Crossroad” started to operate in Zatonie, which would become Bogatynia’s northern district in 1973, and a day care centre called “Under the Lamb” started to operate in nearby Trzciniec. At that point, Bogatynia still looked like a large village with long streets and buildings scattered along them: it had been a village for most of its history and even today does not have a typical urban layout. A sewerage system was opened here in 1945. Some people, discouraged by the prevailing conditions, leave7.

– There was no community for Bogatynia in the first years, nor for the mine. In fact, people lived here from month to month

– summarises Adam Szpotański, a researcher of regional history8.

It was not until – or perhaps already? – in 1949, Stanisław Hofman, one of the pioneers of the Polish mine crew and the creator of the first system of standards and reporting in the plant, wrote in his annual report that

“The people who found themselves here by accident have left the mine. Those who have tied their existence, their future, their fate to the mine have remained… “

In 1954, the Turów mine had 1400 employees, and food was no longer transported to the Turoszów Sack by horse-drawn carts – a railway line from Mikulova to Turoszów was opened in 1952. A year later, Polish geologists published the results of a reconnaissance of lignite deposits. They estimated: there were approx. 18 million tonnes. Enough for 45, maybe 50 years of exploitation9.

The real prospects opened up. Back in 1946, during the talks on the transfer of the mine, the Polish delegates had learned that the Soviet Administration had intended to open another open pit within two years specifically for the Hirschfelde power plant, on the left bank of the Lusatian Neisse. In the short term, coal from Turow would no longer be needed by Hirschfelde – or at least most of the extracted raw material would remain in Poland10. Therefore, it could be utilised by a new Polish power plant. If only the authorities consider that the post-war borders are stable and will not be redrawn again.

(to be continued)

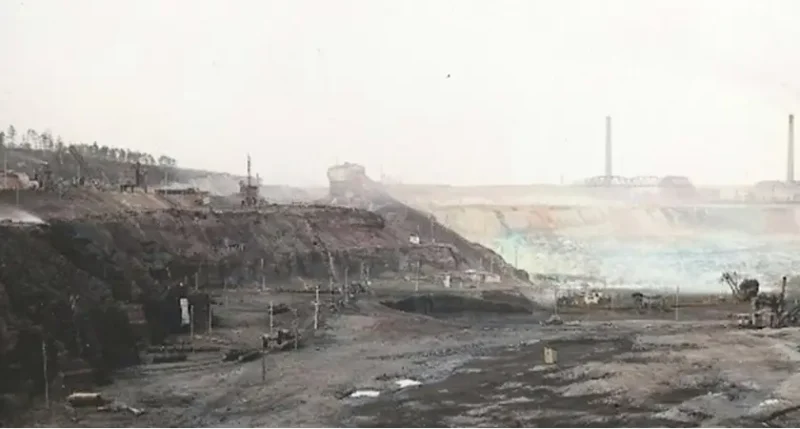

Cover photo: Hirschfelde mine as of 1919. Author unknown. Photo colored by Piotr Lewandowski.

Piotr Lewandowski, Iwona Lewandowska and Czesław Kulesza co-operated in the preparation of this report.

This report was developed with the support of Journalismfund.

- Red. H. Izydorczyk, Kopalnia Węgla Brunatnego Turów 1947-2022, Polska Grupa Energetyczna Górnictwo i Energetyka Konwencjonalna SA, Oddział Kopalnia Węgla Brunatnego Turów, Bogatynia 2022, p. 14. ↩︎

- A. Szpotański, Kotlina Turoszowska. Monografia miasta i gminy Bogatynia w okresie 1945-2010, Biblioteka Diecezji Legnickiej, Legnica 2019, p. 114; Kopalnia Węgla Brunatnego…, p. 15. ↩︎

- Z. Dobrzyński, Płynie struga węgla: opowieść o turoszowskiej braci, Kopalnia Węgla Brunatnego Turów, Bogatynia-Zgorzelec 2002, p. 34-35. ↩︎

- A. Szpotański, Kotlina Turoszowska, p. 116; Z. Dobrzyński, Płynie struga węgla, p. 35-36; red. H. Izydorczyk, Kopalnia Węgla Brunatnego…, p. 15. ↩︎

- Bogaty means rich in Polish. ↩︎

- National Archives in Wrocław, Bolesławiec Section [Archiwum Państwowe we Wrocławiu, Oddział w Bolesławcu], coll. 32, nr 49, p. 1. ↩︎

- A. Szpotański, Kotlina Turoszowska, p. 73 and 115-117; Z. Dobrzyński, Płynie struga węgla, p. 34-35 and 42-43. ↩︎

- A. Szpotański, Kotlina Turoszowska, p. 117. ↩︎

- A. Szpotański, Kotlina Turoszowska, p. 116-119. ↩︎

- Z. Dobrzyński, Płynie struga węgla, p. 27-28. ↩︎

![Jiu Valley: is there a life after coal? [GALLERY]](https://www.foundintransition.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/wieza-wyciagowa-i-chmury-scaled-1200x675-1-600x400.jpg)

![Jiu Valley: is there a life after coal? [GALLERY]](https://www.foundintransition.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/wieza-wyciagowa-i-chmury-scaled-1200x675-1-120x120.jpg)

![There is no just transition without trust and social capital [interview]](https://www.foundintransition.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Paroseni-scaled-1200x675-1-600x400.jpg)

![There is no just transition without trust and social capital [interview]](https://www.foundintransition.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Paroseni-scaled-1200x675-1-120x120.jpg)

11 Comments

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of Socialist Poland - Cross-border Talks

30 September 2023[…] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART FOUR: First Worries About the Water - Cross-border Talks

9 October 2023[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Turów case [PART FIVE: At Any Cost] - Cross-border Talks

14 October 2023[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Turów case. PART SIX: There Is No Plan - Cross-border Talks

30 October 2023[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART SEVEN: Arrogance and Lack of Empathy - Cross-border Talks

4 November 2023[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART EIGHT: Barriers and water pipes - Cross-border Talks

13 November 2023[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART NINE: Czech Skeletons in the Coal Closet - Cross-border Talks

22 November 2023[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TEN: Paradoxes - Cross-border Talks

7 December 2023[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART ELEVEN: There will be nothing without the mine - Cross-border Talks

18 December 2023[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TVELVE: Uncertainty - Cross-border Talks

5 January 2024[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THIRTEEN: Past Covered in Coal, Future Uncertain - Cross-border Talks

27 January 2024[…] Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine [PART ONE] Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TWO: In the New Poland Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THREE: Pride of […]