Read previous chapters of the story:

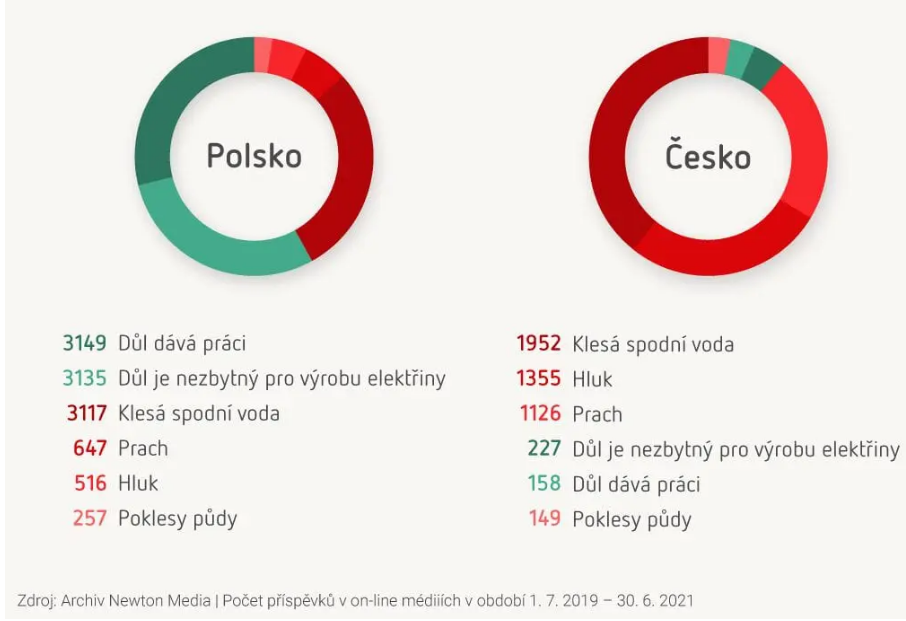

It is true that in the Czech media discourse, the Turow mine was presented more from an environmental perspective as a problem of mining impacts, while in Poland social arguments were much more dominant. Newton Media’s 2021 analysis shows that media in the Czech Republic and Poland in 2019-2021 talked about “two Turóws.” The analysis also notes that in the Polish case there was little media engagement with Polish trade unionists. The media coverage of Turow’s problems was dominated by the Polish company PGE, which, paradoxically ,talked about the threat of job losses as “its” argument. It is not easy to guess why and to what end.

Analysts at Newton Media have been studying online media content for a year, and their analysis shows quite clear differences between the arguments for (green) and against (red) between the view from the Czech Republic and the view from Poland.

Source: Newton Media

Not seeing the history of the mine dispute from the other side naturally leads to further misunderstandings. Therefore, let’s also look at the Polish situation.

Currently, the Czech Republic, Poland and Germany are among the countries that use coal as an energy source to the greatest extent in the EU. In particular, coal plays a significant role in Poland’s energy mix. According to the International Energy Agency, Poland is heavily dependent on fossil fuels:

“Fossil fuels continue to dominate Poland’s energy supply (85% of total energy supply in 2020), with coal accounting for the largest share (40%), followed by oil (28%) and natural gas (17%). Coal plays a key role in the Polish energy system and economy.”

By comparison, according to the MEA, coal accounts for about one-third (about 33%) of the Czech Republic’s total energy supply, although its role declined by 19% between 2009 and 2019.

Among the agency’s member states, Poland is one of the countries with the highest share of coal in both total energy supply and total final consumption in 2020, and coal-fired heat generation ranks second among member states. However, Poland was and is also affected by the shift away from coal: between 2010 and 2020, the share of coal in the national energy mix declined, coal mining in Poland also declined, and Poland became a net importer of coal. As of 2021, coal has made a comeback, and according to the IEA, energy production from coal has returned to 80%. However, the importance of coal has increased across the EU as a result of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Add that Poland does not yet have a single nuclear power plant – although it is currently planning to build one – and despite its success in introducing alternative, renewable energy sources, moving away from fossil fuels is a long road.

For Poland, coal means not only electricity and heat, but also jobs.

For the region around Bogatynia and for Lower Silesia as a whole, it is even more fundamental. In 2021, Poland’s defense argued before the European Court of Justice that the closure of the Turów mine would put a total of 15,000 people out of work. The district of Zgorzelec, which territorially includes Bogatynia, has a population of slightly less than 90,000 (2019), which in raw numbers would mean that about 16% of people would be unemployed. Speaking to our Polish colleagues, the Turow mine union leader Bogumil Tyszkiewicz stated that closing the mine would be a social disaster for Bogatynia and the entire region. Not surprisingly, the Polish reaction to the lawsuit against the Czechs was very emotional, especially when the court ordered the mine to be closed until a final verdict was reached.

Zuzana Pechová of the Uhelná Neighborhood Association says the issue of jobs is also sensitive for their neighbors in the Czech Republic. The goal of their campaign against the expansion of the mine near their homes was never to immediately close the mine and take away people’s jobs.

“Of course, and none of us has said anywhere that we want the mine to close immediately. We are often vilified for this…. Of course, it is clear to us that this issue is a long-term one and that the transformation will take some time. Since the mine is located in the immediate vicinity, we care about both nature and neighborly relations, so that people living a few kilometers away from us are not left without work to take care of themselves and their families.”

In its report on the impact of the coal phase-out on Poland’s Lower Silesia region, the World Bank says that coal employment in Poland is the highest in the entire EU. In 2019, it was about 155,000 people. By comparison, the Czech Republic ranks third in the EU with about 22,000 people working in this sector of the economy, according to 2019 data. In the case of Lower Silesia,

“the PGE Group is one of the largest employers in the region and the largest energy company in Poland, consisting of entities involved in the production of electricity through lignite mining, electricity generation and distribution, and electricity trading.”

However, the decline in employment in this sector of the Polish economy has continued uninterrupted since 1989, and is related to the declining role of coal, the main factor of which was not so much environmental, but rather economic. The share of direct employment in this sector has fallen by 80% in Poland, while in 1989 there were about 450,000 people working in it.

The town of Bogatynia grew up together with the coal mine, and today, too, the inhabitants say that without coal, there will be hardly any opportunities here. Photo by Piotr Lewandowski.

It is estimated that in 2020 there will be about 84,500 people working directly in the coal sector in Poland. However, indirect jobs in the coal value chain should also be taken into account.

Mining creates additional jobs in companies that provide other services and goods. In addition, there is also a so-called induced impact in local communities – much of the demand for locally produced goods and services in local communities (and related jobs) comes from the wages of coal miners and related workers. In the case of the Turow area, this is indeed true, although in the perspective of Poland as a whole, it is less than 1% of the Polish workforce.

PGE is a major employer in Zgorzelec and Bogatynia, but in addition to this, the state-owned company is also important for indirect jobs. “More than nine out of every ten coal-related jobs in Lower Silesia are located in the PGE group,” – notes the World Bank. “Turów and its subsidiaries employ nearly a quarter of the workers in small and medium-sized enterprises and large enterprises (employing 10 or more people) in the Lower Silesian district.”

In other words, much of the region is heavily dependent on PGE and coal mining, making the coal phase-out and eventual closure of the mines and power plants a major social and political problem.

It is already clear that the region will need conceptual assistance in such a transition. However, it is also clear that the move away from coal will happen sooner or later at Turow. Insisting on continued mining, however, will deprive this heavily coal-dependent region of EU financial support under a Just Transition. While EU subsidies are certainly not self-sustaining, this will mean that the costs of the social and economic “rehabilitation” of the closure will be borne by Poland itself.

Czech neighbors across the border, therefore, do not understand attitudes across the border and consider them short-sighted with regard to the future:

“We are sad about two things. One is the unfair agreement and a kind of betrayal of our Czech politicians towards us, and the other thing is the attitude of the Polish government and the company or mine owner towards the future of the mine, because by agreeing to mine until 2044, they will not receive money from the transformation fund …. and they won’t get the opportunity to transform the region.”

– Zuzana Pechová of Uhelna told us.

In her opinion, it almost looks as if the Polish side “doesn’t care about the region and just leaves it fallow.” According to Nikol Krejčová of Greenpeace, the Polish region lacks concrete plans to move away from coal, and such an attitude is irresponsible “towards the region and these people, because they are hostages to the coal business.” Her colleague and Greenpeace Czech Republic spokesman Lukáš Hrábek believes that the Polish government and the mining company have “in a sense sacrificed” the people of the region around Turow.

Czech skeletons in the coal closet

The Czech Republic’s lawsuit against Poland over the Turow mine expansion was also an attractive topic, as it dispelled long-standing myths in the Western press about the homogeneity of the Visegrad Group and fit well with Poland’s generally negative media reputation under the EU Law and Justice government. This brought into play emotions that had little to do with the case. Formally, the lawsuit was based on the fact that Poland had violated a European directive, and thus European law and its compliance, by allowing mining in Turow. In general, it was about something more.

In the court proceedings, there was an argument that prioritized irreversible environmental effects over temporary socio-economic effects in assessing the future of the mine. This argument by the Czech side, ironically a country with a relatively strong fossil fuel lobby, found support in the court proceedings. Among other things, the court stated that the inability “to implement significant energy projects and investments can in no way outweigh environmental and human health considerations.” In other words, jobs can be replaced by targeted social and economic policies, but damaged health and nature cannot. We can speculate whether such a ruling would be particularly good news for the fossil lobby in the Czech Republic or Poland (and elsewhere) if it became the rule in assessing the pros and cons of mining.

Polish critics point out that there is a double standard in the Turow case. After all, open-pit coal is also mined in the Czech Republic with similar negative consequences. They were right, of course, although the nuances of cross-borderism were forgotten. Playing on the fact that one country’s sovereignty takes precedence over the needs and interests of another country, in addition in such a specific geographic area, smacked of arrogance and an inability to find compromises based on goodwill. However, this does not absolve the Czech Republic of its own “skeletons in the coal closet.”

Moving away from fossil fuels will be difficult for the Czech Republic, and moving away from coal affects three regions of the country, not coincidentally the socially and economically weakest.

In all cases, black gold has affected the local economy and nature, and the shift away from coal and the 1990s transition have made things even worse. Misguided and short-sighted policies have left the coal regions of the Czech Republic (and beyond) facing serious problems, such as structural unemployment in the first place. However, this transition also concerns the Czech energy system, and from what sources will a country with an energy-intensive industry draw electricity in the future? Under the current system, it is impossible to separate social and economic considerations from the undoubtedly harmful actions of the current and still prevailing exploitative paradigm. Unfortunately, the goal of current EU climate policy is not to change a system built on the continued exploitation of natural resources. Lithium mining, for example, is already considered environmentally demanding, while experts acknowledge that the socio-environmental effects of mining are poorly studied. Moreover, the demand for lithium has a socioeconomic dimension in the Global South, where it reinforces inequality and deepens the dependence of local economies. For the Czech Republic, this is a topical issue, given the relatively large lithium deposit at Cínovec in northern Bohemia, with which the current government of Prime Minister Petr Fiala seems to have high hopes.

But back to coal. Bohemian Turow today is an open-pit mine in Bílina, North Bohemia, operated by Severočeské doly, a member of the ČEZ group, with a total workforce of about 2,500 (2020). The Bílina openpit covers about 18 square kilometers and is about 200 meters deep, which means that mining here takes place at sea level.

View of Bilina mine. Photo by MAKY.OREL (CC-BY-SA 4.0)

Compared to Turow, however, Bílina is slightly smaller (28 sq. km) and less deep (225 meters). Between 8 and 9 million tons of coal are mined here annually (27.7 million tons at Turow). In the 1970s, the mine development led to a destruction of several villages. The Bílina quarry also supplies the nearby Ledvice thermal power plant, which, unsurprisingly, belongs to the CEZ group and has a capacity of 770 MW after modernization. In 2020, it was responsible for 2.4% of all emissions in the Czech Republic. According to environmentalists from Greenpeace, mining at the Bílina quarry “generates thousands of tons of dust every year, excavators rumble and reduce the quality of life in the surrounding villages of Mariánské Radčice and Braňany. In neighboring villages, this threatens not only the health of people, but also the existence of some protected bird species.”

Despite this, Andrej Babiš’s government (yes, the same government that sued Poland) has agreed to continue mining until 2035, breaking mining limits.

Greenpeace spokesman Lukáš Hrábek compared the Turow and Bílin mines for us.

“In both cases, the state-owned company is pushing for an extension of mining. In both cases there are large coal reserves. There is the possibility of mining in the long term. In both mines there is the possibility of extending mining beyond the original permit…. What is different about Turow is that there the case is practically closed, and all Polish politicians, including Environment Minister Anna Moskwa, have been clearly and openly fighting for the fossil industry and trying to negotiate the best possible terms for it. Here, many politicians do not express such support for the fossil fuel business and are not fighting to keep it going.”

According to Hrábek, as of May 2023, the procedural issue in the Bilina case has not yet been resolved.

In March 2023, Severočeské doly received a mining permit until 2030 from the Mining Authority. The current permit is valid until 2030, and the company wants to prepare for the possibility of mining until 2035, “if we are able to ensure national energy security.” In 2015, Bohuslav Sobotka’s government authorized mining in Bílina, exceeding limits set in the 1990s. It is true that the ANO movement imposed conditions during government negotiations, including that the quarry not be located at least 500 meters from local villages. The argument was not to worsen the living conditions of people living near the quarry. Local municipalities demanded that Severočeské Mines strictly adhere to protective measures and stay away from the quarry, but otherwise had no problem with expansion on an official level. The protective measures included, among other things, a 3.3-kilometer-long green belt, whose construction began in 2011. The Bílina decision was a compromise. The government rejected the expansion and continuation of the CSA mine, with coal mining halted in 2021. But it was also a compromise because it took into account the conditions of local communities, which are often also economically dependent on mining.

The difference between Turow and Bilina is not just the size and the fact that dewatering is not as big a problem at Bilina, although both mining operations undoubtedly have a number of negative impacts (dust, noise, emissions, landscape destruction). The difference is not just a matter of circumstances and a different context. The difference is also created by the fact that people on the other side of the border, in the Czech Republic, feel only the negative effects of mining in Poland, while they are not economically dependent on mines and mining operations and do not receive any tangible benefits that would at least materially “compensate” for the negative effects. Turów is not a matter of “vested interests” of people on the Czech side of the border. This interdependence was missing in the case of the Turów mine, and the Polish side tried to ignore it, repeating the thesis of Polish national interest and sovereignty. Hence the existence of “two Turów” – Czech and Polish – throughout the dispute.

Bílina is, of course, not the only mining site in the Czech Republic, as indicated by the relatively high share of coal in the Czech energy mix (33%). The main players in the fossil energy and coal markets are the parastatal CEZ, which some Czech journalists consider or have considered in the past to be more “powerful” than the government. In 2010, Britain’s The Economist noted CEZ’s prominent position, writing of the Czech company that “although (it is) nominally owned by the state, many see power moving in the opposite direction – from CEZ to politics.” Such metaphors attempt to describe the company’s unique position as a producer, distributor and exporter in the Czech market and in politics. CEZ’s operations include not only coal, but also nuclear power, gas and water and other renewable sources. In total, it employs some 28,000 people in the Czech Republic (2022). Incidentally, the second-largest Czech company also has operations in Poland, where it operates two coal-fired power plants – Chorzow in Silesia and Skawina in Malopolska.

CEZ is not the only player operating in the Czech energy market with an interest in coal mining. The holding company describes itself as a “vertically integrated energy company covering the entire value chain: from lignite mining, to electricity and heat production, to electricity and heat distribution.” It comprises some 70 companies and employs around 11,000 people (2020). In addition to energy, Křetínský also invests in other areas, including soccer and media. Currently, his company Czech Media Invest (CMI) owns Blesk, the most widely read Czech tabloid, or Info server (through another company, Czech News Center, owned by CMI). But Křetínský has invested in media in six or seven other countries in Europe, and his stake in France’s Le Monde has attracted the most attention abroad. It is probably no surprise that Daniel Častvaj, who also served as director of communications and marketing at ČEZ, is now a member of CMI’s board of directors. This is by no means Křetínský’s only connection to ČEZ. Incidentally, Mirek Topolánek, former president of ODS and prime minister of the Czech Republic (2006-2009), also works for Křetínský’s EPH. Acting in the media is a very clever move. Recently, in 2019, Czech researchers from Masaryk University in Brno showed that Czech media discourse has long separated coal mining from coal combustion, which, in their view, leads to

“neglecting the inevitable link between the two processes; coal consumption is not described as an environmental problem, and the economic problems of private companies more easily become public problems, making it difficult to implement future coal phase-out policies.”

Finally, there is Pavel Tykač’s other energy company, Sev.en, which mainly produces electricity from coal and employs more than 3,000 people. The company is based in Liechtenstein and is owned by Tykač’s Cypriot company. In 2019, Tykača-owned Sev.en acquired the Počerady thermal power plant in the Vyškov region (the largest eminent in the Czech Republic in 2020) from CEZ, where Sev.en also owns the Vršany coal quarry. According to experts, Počerady is one of the most polluting power plants in the Czech Republic, and the Vršany quarry has brought a number of very negative effects to the surrounding areas. It was Tykač’s company that tried to enforce the violation of mining limits at the ČSA mine in northern Bohemia, which it owns, but despite pressure, the Sobotka government decided not to allow mining limits and to halt mining. However, Tykač is definitely not focused solely on the Czech energy market. According to a recent Reuters report, the Czech miner is looking to invest in the U.S. and Australia, all in the fossil fuel industry, and coal in particular. “The world of coal and fossil fuels is so badly financed that it makes assets much cheaper because they have to be financed with equity,” Tykač said in May 2023. Tykač then added that the fossil industry will be phased out, but for now it offers high returns: “No doubt it will end one day, but at the moment there are opportunities in this sector and we don’t think there will be any great rush, there is a demand for power plants.” Bloomberg noted in April of this year that Kretinsky bet against the EU’s green strategy and got rich by “buying everything that burns.” Tykač and Křetínský thus appear to be betting on a slow shift away from coal in their strategy. In particular, EPH as a whole has set an ultimate goal for a carbon-free future (2050), and its subsidiary EPIF has set a target of 2040, while Tykač’s company has apparently not yet set a date. Incidentally, CEZ postponed its transition to carbon neutrality from 2050 to 2040 in 2022.

Although Tykač made it clear in May that there is “no rush” for its new foreign acquisitions, the situation in the Czech and European context may be different. This is due to cheaper electricity prices combined with expensive emission allowances (the price of which is expected to rise in the future), Seznam reported. Here we encounter another paradox of the current development. According to the plans of the Petr Fiala government, coal will cease to be a source of energy in the Czech Republic in 2033, eleven years earlier than in Poland. However, the political decision may have nothing to do with market realities, which are decisive in the current system and are certainly the main motivation of businessmen such as Tykač and Křetínský, or the semi-state-owned ČEZ. The relatively low price of electricity on the market and the high price of emission allowances is a combination that will not be economically beneficial. “As the price of electricity falls, production will probably cease to be profitable in 2025. 2026 will, of course, be a loss-making year, and 2027 looks like a total disaster for our coal power industry,” – Pavel Tykač admitted in June 2023.

Neither he nor ČEZ intends to continue unprofitable operations, which, however, confronts the country with the question: what will replace coal as an energy source in the event of a too rapid withdrawal from coal? It seems that the Czech Republic is not prepared for the rapid end of coal and, unlike Poland, has no mechanism for paying for coal capacity to support loss-making coal sources. The Czech government is currently looking for ways to phase out coal and is preparing a new State Energy Concept until 2040. The current 2015 concept was expected to become obsolete and envisioned a “steady reduction” of coal’s role in the energy mix, while increasing electricity consumption to 80 TWh in 2040.

The paradox, then, may be that a faster transition away from coal in the Czech Republic will certainly not be motivated by climate change or environmental concerns of the big players in this rapid scenario. In particular, the Czech Republic is not ready for it in terms of energy, despite warnings from many experts.

According to the current model of CEPS, the Czech transmission system manager, a rapid end to coal between 2030 and 2033 is not an optimal scenario for the Czech Republic, as it will bring severe electricity shortages, as well as high costs. In the event of a sudden, economically motivated end to coal, the Czech state will be left with a “Black Peter” in the form of the loss of an important energy source and jobs: the coal sector currently employs about 22,000 people, but an electricity shortage would have broader and potentially catastrophic consequences for the entire Czech economy. Experts do not yet agree on whether the right combination for the Czech Republic is nuclear power, gas with renewable energy sources (RES), or primarily (and which) RES, which the Czech Republic currently has problems with and has so far been questionable in terms of energy storage. It now seems likely that the Czech Republic will have to import energy. Such a development, if it occurs, will be another paradox, as energy prices and other changes are very difficult to predict. The Czech Republic has long been an exporter of electricity under the current and declining economic model.

(to be continued)

This report was developed with the support of Journalismfund.

Piotr Lewandowski, Iwona Lewandowska and Czesław Kulesza co-operated in the preparation of this report.

Subscribe to Cross-border Talks’ YouTube channel! Follow the project’s Facebook and Twitter page! And here are the podcast’s Telegram channel and its Substack newsletter!

Like our work? Donate to Cross-Border Talks or buy us a coffee!

![Jiu Valley: is there a life after coal? [GALLERY]](https://www.foundintransition.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/wieza-wyciagowa-i-chmury-scaled-1200x675-1-600x400.jpg)

![Jiu Valley: is there a life after coal? [GALLERY]](https://www.foundintransition.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/wieza-wyciagowa-i-chmury-scaled-1200x675-1-120x120.jpg)

3 Comments

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART ELEVEN: There will be nothing without the mine - Cross-border Talks

20 December 2023[…] for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART EIGHT: Barriers and water pipes Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART NINE: Czech Skeletons … Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TEN: […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TVELVE: Uncertainty - Cross-border Talks

10 January 2024[…] for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART EIGHT: Barriers and water pipes Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART NINE: Czech Skeletons … Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TEN: Paradoxes […]

Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART THIRTEEN: Past Covered in Coal, Future Uncertain - Cross-border Talks

3 August 2024[…] for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART EIGHT: Barriers and water pipes Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART NINE: Czech Skeletons … Lost Opportunity for a Just Transition: the Case of Turów Lignite Mine. PART TEN: Paradoxes […]